You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

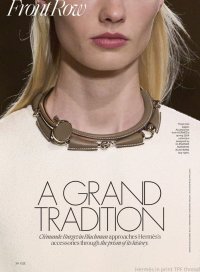

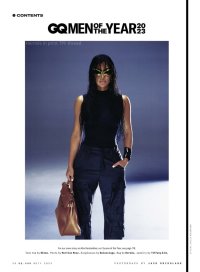

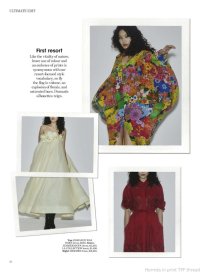

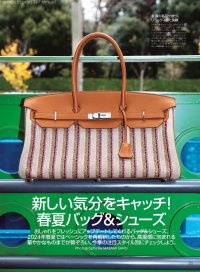

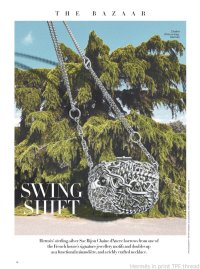

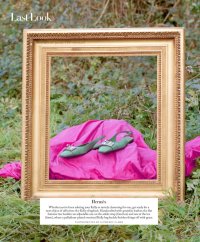

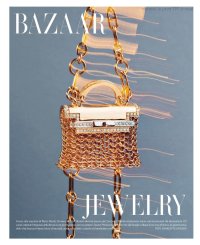

Hermes in print

- Thread starter HiHeels

- Start date

TPF may earn a commission from merchant affiliate

links, including eBay, Amazon, and others

More options

Who Replied?Hermès Q4 Sales Up 18% As Ready-to-wear, Watches and Beauty Soar

The company is proving resilient in the face of slowing luxury spending, with growth in other categories outpacing its solid leather goods business.

PARIS – Hermès is still leading the pack.

The French luxury leather goods company is proving to be resilient in the face of slowing luxury spending, with sales up 18 percent in the fourth quarter at constant exchange rates to 3.36 billion euros.

Growth in the Americas was particularly strong in the three-month period to Dec. 31, with sales up 21.6 percent. Sales in Asia were up 14.8 percent at constant exchange rates, with Japan jumping 26.2 percent.

Those growth numbers put it ahead of LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton, whose sales were up 5.5 percent in the fourth quarter and far ahead of rival Kering, whose sales fell 6 percent in the three months to Dec. 31.

“In 2023, Hermès has once again cultivated its singularity and achieved an outstanding performance in all métiers and across all regions against a high base. These solid results reflect the strong desirability of our collections and the commitment and talent of the house’s women and men. I thank them all warmly,” said Hermès chief executive officer Axel Dumas.

The company topped 13.42 billion in sales for the full year, up 21 percent at constant exchange rates, with a net profit of 4.31 billion euros.

The company continued “its strong brand momentum,” said Bernstein analyst Luca Solca. The numbers put it above consensus that had predicted a 13.7 percent growth.

“Importantly leather goods is ahead and double digits in the quarter, defying the usual end of year lull on the back of satiated store managers having met targets long before. Hermès is yet another company to confirm reviving momentum of the American consumers, on the back of resurgent confidence and lower inflation,” he said in a note after the release on Friday.

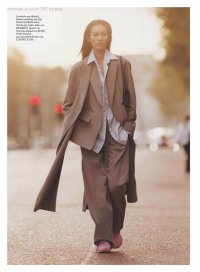

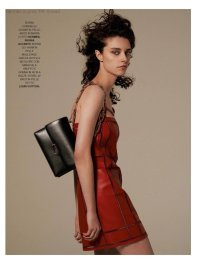

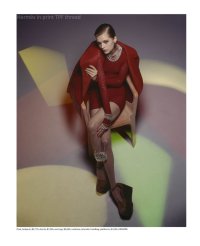

The company, famous for its Birkin and Kelly handbags, has been strengthening its other categories in recent quarters, with growth in the ready-to-wear and watches categories outpacing its core leather goods category. That trend continued over the holiday period, with ready-to-wear jumping 27.5 percent, while sales of leather goods were up 10.4 percent.

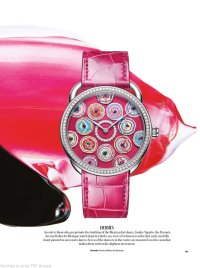

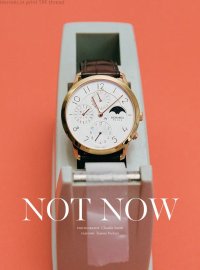

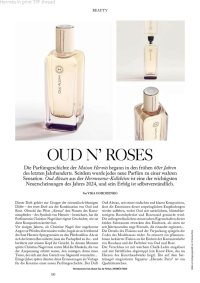

Beauty, an accessible and expanding category for the company, and its watch division both clocked 22 percent growth in the fourth quarter.

The company is combating the luxury sector’s recruitment issues with another bonus for employees, and will pay 4,000 euros to all staff worldwide as a reward for the year’s stellar results.

Consumers are spending on jetting around the world, benefiting Hermès wholesale activities, which were up 24 percent driven by the travel retail business in 2023.

Looking ahead, the company sees itself staying steady despite the geopolitical headwinds and slowing economic growth in other categories, as consumers become more cautious about their spending.

“In the medium-term, despite the economic, geopolitical, and monetary uncertainties around the world, the group confirms an ambitious goal for revenue growth at constant exchange rates,” it said in a statement.

Hermès Q4 Sales Up 18% As Ready-to-wear, Watches and Beauty Soar

Hermès International (RMS) Q4 2023 earnings are in: sales rose 18 percent on strength of ready-to-wear, watches and beauty.

Hermès Taps Architect Lina Ghotmeh to Create the Saddle Workshop of the Future

The French region of Normandy is home to the company’s 21-century atelierBy Dana Thomas

August 11, 2023

Architect Lina Ghotmeh and Hermès artistic executive vice president Pierre-Alexis Dumas outside the workshop.Photo: Yann Stofer.

In Normandy, Hermès’s new Maroquinerie de Louviers features arches of locally made brick.

Photo: © Iwan Baan

For its first saddle workshop outside its historic Paris headquarters, Hermès chose the equestrian region of Normandy, in the commune of Louviers. As the company’s artistic executive vice president, Pierre-Alexis Dumas, noted at the inauguration in April, “Thierry Hermès was a saddlemaker for 10 years in Normandy before starting the company in the mid–19th century.”

Inside the atelier.

Photo: © Iwan Baan

Even with this respectful nod to the past, the Maroquinerie de Louviers, designed by French Lebanese architect Lina Ghotmeh, is 100 percent 21st century in concept, with eco-responsibility at the forefront. For the construction of the 66,700-square-foot building, which sits on some 10 acres, Ghotmeh commissioned local artisans to hand-make the half million red bricks that now enrobe the pinewood frame, minimizing carbon emissions with what she calls “materials from nature” while supporting traditional Norman craft.

Hermès Cavale II Saddle.

Photo: Courtesy of Hermès.

To power the space, there is geothermal energy and nearly 25,000 square feet of solar panels. Low-consumption LEDs, skylights, and north-facing windows illuminate the atelier with diffuse light, “like an artist’s studio,” Ghotmeh says. For the grounds, Belgian landscape architect Erik Dhont retained most of the existing trees and built a rain-capturing drainage system that replenishes the water table. So green is the Maroquinerie de Louviers, it is the first industrial building in France to earn the E4C2 designation, meaning it is low carbon and energy positive. “It’s almost a piece of nature,” Ghotmeh says. “Like it belongs to the earth.”

Hermès Kelly Sellier 25 bag.

Photo: Courtesy of Hermès.

Ghotmeh is a rising star in architecture, best known for this summer’s Serpentine Pavilion in London, inspired by a shared table, and the 2016 award-winning Estonian National Museum, a wedge-shaped glass building on a former Soviet airfield. The Hermès team was so impressed by the museum’s design (completed while Ghotmeh was a partner at Dorell Ghotmeh Tane / Architects) they invited her to submit a plan for the workshop’s competition in 2019. The 35-member jury unanimously chose her proposal, which is rooted in classical design, with

a series of Roman aqueduct-like arches for the façade as well as the interior. Their forms, Pierre-Alexis said, “echo the movement of the thread, and handbag handles. There’s a dialogue between the function and the structure.”

Ghotmeh describes her approach as “the archeology of the future,” meaning how a building emerges in its environment and from the memory of its location. How apt, given that during the initial dig, workers discovered a Paleolithic campsite. Eventually, archeologists recovered 3,000 artifacts, including flint tools likely used for leatherwork, and stones to make needles. “What chance to choose such a place for our leather workshop,” Pierre-Alexis said.

The arch idiom continues inside.

Photo: Iwan Baan

To give the Maroquinerie de Louviers a bit of artistic flair, Hermès tapped French artist Emmanuel Saulnier to create a sculpture of seven 10-feet-long needles in sleek stainless steel, suspended above the entrance in stirrup leathers sewn by Hermès bridle makers. Pierre-Alexis described the artwork as a “symbolic gesture to represent this workshop now where there had been one so long ago.”

When the workshop is at full capacity, it will employ 260 artisans, handcrafting made-to-order saddles—including for French Olympic gold medalist eventer Astier Nicolas—as well as classic Kelly handbags. Many of the workers will come from the Louviers École Hermès des savoir-faire, an education facility that opened in town last year. As Hermès executive chairman Axel Dumas told the workshop’s artisans before cutting the ribbon: “We are making beautiful objects in beautiful surroundings.” hermes.com

Hermès Taps Architect Lina Ghotmeh to Create the Saddle Workshop of the Future

The French region of Normandy is home to the company’s 21-century atelier

Interesting FT article about luxury consumers starting to curb their spending on luxury good as the feeling of exclusivity fizzles out in luxury brands’ attempts to grow their customer base. We’re seeing that sentiment expressed on the forum, too.

Excerpt from the article:

“At what point does paying astronomically higher prices for what have become more mainstream products stop making sense? Many luxury houses may need to revert to being more exclusive if they want to justify their products’ cost. Endlessly expanding luxury’s customer base while also increasing prices cannot go hand in hand forever.”

Excerpt from the article:

“At what point does paying astronomically higher prices for what have become more mainstream products stop making sense? Many luxury houses may need to revert to being more exclusive if they want to justify their products’ cost. Endlessly expanding luxury’s customer base while also increasing prices cannot go hand in hand forever.”

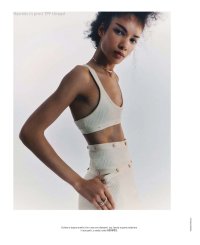

Will She Make the Next Birkin?

A bag designer at Hermès has the fun and formidable challenge of creating a new icon. No presh.By Marisa Meltzer

Reporting from Paris

March 13, 2024, 5:00 a.m. ET

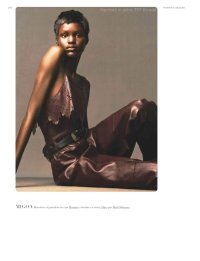

Priscila Alexandre Spring, who was appointed the creative director of leather goods at Hermès in 2020.

Maxime La for The New York Times

She first does a sketch, which she then takes to the prototype makers, who discuss size, functionality, even the sound of the hardware.

Maxime La for The New York Times

“The bag, it carries your things and carries your secrets,” Priscila Alexandre Spring said. The 43-year-old creative director of leather goods at Hermès sat in her office in Pantin, just outside of Paris, explaining what she liked about designing bags — in particular, the relationship between “your private life and your exterior life.”

Ms. Alexandre Spring joined the Hermès leather goods métier in 2015, and in 2020 she was appointed to her current role. Hermès, which began in 1837 as a saddle maker, is a name that comes with intimations of money (bags often sell for more than $10,000), scarcity (if you can get your hands on one) and craftsmanship (each is handmade by a single craftsperson). Most people have heard of the Kelly bag (named for Grace Kelly) or the Birkin (named for Jane Birkin) and the myriad celebrities who tote them.

It is Ms. Alexandre Spring’s job to make the next big one.

Born in Canada, Ms. Alexandre Spring grew up in the south of Portugal. Her Portuguese father and Mozambican mother were both teachers who wanted their daughter to be curious about the world and have a classic education. She learned five languages (English, Portuguese, Spanish, French, Italian) and studied piano, flute, violin and ballet.

At 13, she switched to basketball, which she played until she was 25. “Maybe this is why, for me, it’s really important to work within a team,” Ms. Alexandre Spring said. She keeps an Hermès baseball glove in her office alongside stacks of art books — “Margiela: Les Années Hermès,” Jamel Shabazz’s “A Time Before Crack.”

She studied fashion design at the Lisbon School of Architecture, then moved to Paris and bounced around design houses, working first for the Portuguese designer Felipe Oliveira Baptista, then designing men’s ready-to-wear for Louis Vuitton, then as an accessory stylist for Balenciaga. She moved to New York in 2008 to join Proenza Schouler.

Assorted Hermès bags share space alongside stacks of art books in Ms. Alexandre Spring’s office.Credit...Maxime La for The New York Times

In New York, she lived mostly in the East Village and freelanced, designing shoes for Marc by Marc Jacobs. “Downtown New York, it’s like a small town,” she said. Soon enough, she ran into Humberto Leon and Carol Lim of the erstwhile cool-kids boutique Opening Ceremony, who hired her in 2010.

When Mr. Leon and Ms. Lim became the designers of Kenzo, Ms. Alexandre Spring joined them in Paris as an accessory stylist, splitting her life between France and the United States, 15 days at a time. After a year of back and forth, she moved back to Paris full time.

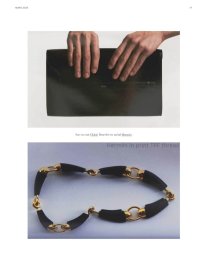

Ms. Alexandre Spring, who lives with her American husband and two children in the Marais, likens the design process to a pingpong game: a dialogue between her fellow designers and artisans. As a first step, she’ll do a sketch, which she then takes to prototype makers, whose workshop is just a few steps away. They discuss size, functionality, even things like the sound the hardware makes when the bag closes.

For the Arçon bag, Ms. Alexandre Spring was inspired by the shape of the flap of a saddle. But then another inspiration came to her, she said.

“I was looking at a book that was talking about pockets in the 19th century, how men had about seven pockets in their jackets, pockets in their little vests and pockets in their pants, and women could have only one pocket that they had to hide under their skirt. And that was kind of the beginning of emancipation of women. When skirts became smaller and tighter to the body, they just took the pocket up from under the skirt and put it outside.”

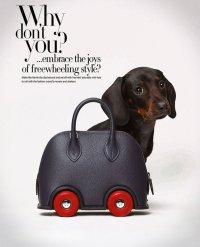

The Petite Course is “for a sports car,” Ms. Alexandre Spring said. “You put your wallet and your keys in it and you go.”

Credit...Maxime La for The New York Times

When she designed the Hermès Arçon bag, Ms. Alexandre Spring was inspired by the flap of a saddle.

Credit...Maxime La for The New York Times

“So that’s how this pocket came here,” she said, pointing to an angled zip pocket, reminiscent of a slash pocket on a skirt or trousers, on a chocolate brown Arçon. A hook was added for keys or gloves.

Another bag Ms. Alexandre Spring designed, the Petite Course, which means a little errand in French or a little ride, was smaller, more ergonomic — “for a sports car,” she said. “You put your wallet and your keys in it and you go.

Once Ms. Alexandre Spring and her team are satisfied with a design, they make it out of salpa, a material that is similar to leather, a process she compares to Frankenstein’s monster. “We make them small, we make them big,” she said.

The bag is then produced in one of 22 Hermès leather workshops in France. Among them is Maroquinerie Saint Antoine, a workshop in the 12th arrondissement of Paris, where more than 100 apron-clad employees assemble bags. They are mostly longtime craftspeople but include a class of about a dozen trainees whose prior careers included barmaid, sheep breeder and bus driver.

Among moments of office whimsy (bowls of candy and photos of parties are pasted to the desks), there is the occasional crocodile Birkin or a Haut à Courroies made of Volynka leather salvaged from a 1786 shipwreck, which gave the space a pungent, smoky beef jerky scent.

When asked about potential designs on the horizon, Ms. Alexandre Spring demurred. In one corner of a workshop was a decades-old doctor bag she took from the Hermès archives for potential inspiration. Elsewhere in the workshop, ropes were coiled on a table.

“Everything is a work in progress,” she said. “But, yeah, we’re trying a new thing with ropes, but we don’t know if it’s going to work.” It can take between six months and six years to create a new design.

Her team produces 10 new bags for each season for the men’s and women’s collections, which, according to Ms. Alexandre Spring, “is not a lot compared to places where you can have collections of 30 new bags.”

“But sometimes,” she said, “I can think of 10 bags a day.”

Register on TPF! This sidebar then disappears and there are less ads!