From AnOther Magazine:

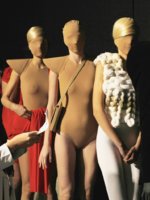

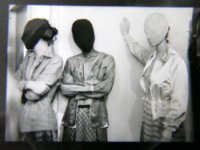

Photography by Anders Erdström; Studio des Fleurs

Photography by Anders Erdström; Studio des Fleurs

Exploring the World of Margiela, the Hermès Years

Susannah Frankel explores why Margiela's unlikely appointment at Hermès made for one of the most successful collaborations in fashion history

— April 4, 2017 —

When, in April 1997, it was announced that Martin Margiela had been appointed creative director of Hermès, it came as a surprise. This, after all, was the era of the superstar designer: Tom Ford at Gucci, John Galliano at Givenchy and then at Dior, Alexander McQueen at Givenchy, Stella McCartney at Chloé... Margiela founded his fashion house in 1988 with Jenny Meirens, and everyone who cared about his work – and we were and still are many – knows that the designer eschewed the spotlight, having learned from his time working alongside Jean Paul Gaultier that being the face of a fashion house comes at a price: one he was reluctant to pay. Post-Eurotrash Gaultier was overlooked for the Dior job despite talent and an estimable pedigree. Margiela preferred his work to speak for itself. He and the loyal inner circle of creatives with which he surrounded himself guarded his anonymity fiercely.

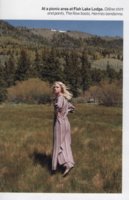

Trenchcoat in cotton gabardine, sleeveless pullover in cashmere and silk, pants in wool, ankle boots in leather, headscarf ‘Losange’ in silk crêpe, Hermès S/S03. Photography by Thierry Le Goues

Trenchcoat in cotton gabardine, sleeveless pullover in cashmere and silk, pants in wool, ankle boots in leather, headscarf ‘Losange’ in silk crêpe, Hermès S/S03. Photography by Thierry Le Goues

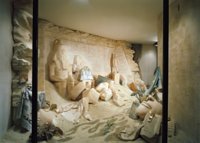

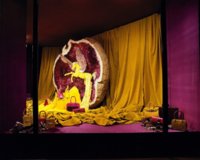

Equally unpredictable – as far as first impressions go, at least – was the choice of a designer who was very much perceived as central to fashion’s avant-garde. Martin Margiela re-worked vintage finds – from leather butcher’s aprons to antique wedding dresses – based clothing around Stockman dummies, home furnishings and even Christmas tinsel. He turned more conventional fashion upside-down and inside-out – often literally – reversing seams and leaving edges to fray. He favoured everyday materials – paper, calico, cheap lining fabrics – and cast beautiful friends and acquaintances as opposed to professional models for his shows, which took place in far-flung places with no seating plan (or at times, even seats). The Maison Martin Margiela label, meanwhile – a blank, white cotton square – seemed to question the very notion of designer fashion as status driven. To the uninitiated, there was no way of knowing that a Maison Martin Margiela design was, in fact, ‘designer’.

Shawl collar cardigan and sleeveless tunic pullover in cashmere, Hermès A/W99, 'Portraits de femme en Hermès', Le Monde d’Hermès, Photography by Joanna Van Mulder

Shawl collar cardigan and sleeveless tunic pullover in cashmere, Hermès A/W99, 'Portraits de femme en Hermès', Le Monde d’Hermès, Photography by Joanna Van Mulder

Hermès, on the other hand, was among the oldest and grandest French status names of them all. Cheap fashion jokes ensued. Would Margiela whitewash the Kelly bag, for example? He loved white – or whites, in Margiela speak – painting leather, denim and more and celebrating the way the non-colour aged thus reflecting the passing of time.

In fact, Margiela’s appointment by then Hermès CEO, the late Jean-Louis Dumas, was among the most inspired in fashion history. Dumas recognised that, at the heart of it all, Margiela was an unrivalled technician. He also saw that at the centre of the Maison Martin Margiela universe, however extreme any tropes might be, was the woman wearing the clothes. His designs may have been groundbreaking but they considered the body inside them over and above anything else.

Vareuse in double-faced cashmere, sleeveless high-neck pullover in cashmere, mid-length skirt in Shetland wool and boots in calfskin, ‘Le vêtement comme manière de vivre’ Le Monde d’Hermès, Hermès A/W98, Photography by John Midgley

Vareuse in double-faced cashmere, sleeveless high-neck pullover in cashmere, mid-length skirt in Shetland wool and boots in calfskin, ‘Le vêtement comme manière de vivre’ Le Monde d’Hermès, Hermès A/W98, Photography by John Midgley

A new exhibition, Margiela, The Hermès Years, at MoMu in Antwerp, is nothing if not testimony to that. At a press conference held in that city on the eve of the opening, Pierre-Alexis Dumas, Jean-Louis’ son and today artistic director at Hermès, told the story of his father’s meeting with Margiela. In place of the elaborate portfolios and moodboards that might have been expected, the designer gave Jean-Louis Dumas a sequence of words. They were as follows: “Comfort, quality, timelessness, everlasting, handmade, tradition, elegance in movement.” That Dumas was able to embrace such an abstract concept – and that Margiela thought in that way in the first place – is nothing short of visionary on both sides. Margiela wasn’t interested in scarf silks or bright colour, something that might have frightened a less pioneering employer given that both were Hermès signatures. Instead, and way ahead of his time, he was intent on the gradual building of a discreetly beautiful wardrobe for discerning women, of all ages, shapes and sizes, assuming, of course, that their budgets allowed. Pierre-Alexis prefers the adjective “costly” to “expensive”, he says with a smile.

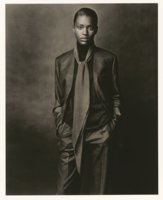

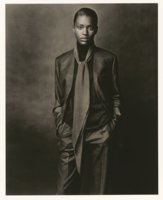

Collarless jacket and pants in cashmere and silk, high-neck pullover in cashmere and silk, scarf ‘Losange’ in silk crêpe, Le Monde d’Hermès, Hermès A/W01, Photography by Ralph Mecke

Collarless jacket and pants in cashmere and silk, high-neck pullover in cashmere and silk, scarf ‘Losange’ in silk crêpe, Le Monde d’Hermès, Hermès A/W01, Photography by Ralph Mecke

cont'd...

Photography by Anders Erdström; Studio des Fleurs

Photography by Anders Erdström; Studio des FleursExploring the World of Margiela, the Hermès Years

Susannah Frankel explores why Margiela's unlikely appointment at Hermès made for one of the most successful collaborations in fashion history

— April 4, 2017 —

When, in April 1997, it was announced that Martin Margiela had been appointed creative director of Hermès, it came as a surprise. This, after all, was the era of the superstar designer: Tom Ford at Gucci, John Galliano at Givenchy and then at Dior, Alexander McQueen at Givenchy, Stella McCartney at Chloé... Margiela founded his fashion house in 1988 with Jenny Meirens, and everyone who cared about his work – and we were and still are many – knows that the designer eschewed the spotlight, having learned from his time working alongside Jean Paul Gaultier that being the face of a fashion house comes at a price: one he was reluctant to pay. Post-Eurotrash Gaultier was overlooked for the Dior job despite talent and an estimable pedigree. Margiela preferred his work to speak for itself. He and the loyal inner circle of creatives with which he surrounded himself guarded his anonymity fiercely.

Trenchcoat in cotton gabardine, sleeveless pullover in cashmere and silk, pants in wool, ankle boots in leather, headscarf ‘Losange’ in silk crêpe, Hermès S/S03. Photography by Thierry Le Goues

Trenchcoat in cotton gabardine, sleeveless pullover in cashmere and silk, pants in wool, ankle boots in leather, headscarf ‘Losange’ in silk crêpe, Hermès S/S03. Photography by Thierry Le GouesEqually unpredictable – as far as first impressions go, at least – was the choice of a designer who was very much perceived as central to fashion’s avant-garde. Martin Margiela re-worked vintage finds – from leather butcher’s aprons to antique wedding dresses – based clothing around Stockman dummies, home furnishings and even Christmas tinsel. He turned more conventional fashion upside-down and inside-out – often literally – reversing seams and leaving edges to fray. He favoured everyday materials – paper, calico, cheap lining fabrics – and cast beautiful friends and acquaintances as opposed to professional models for his shows, which took place in far-flung places with no seating plan (or at times, even seats). The Maison Martin Margiela label, meanwhile – a blank, white cotton square – seemed to question the very notion of designer fashion as status driven. To the uninitiated, there was no way of knowing that a Maison Martin Margiela design was, in fact, ‘designer’.

Shawl collar cardigan and sleeveless tunic pullover in cashmere, Hermès A/W99, 'Portraits de femme en Hermès', Le Monde d’Hermès, Photography by Joanna Van Mulder

Shawl collar cardigan and sleeveless tunic pullover in cashmere, Hermès A/W99, 'Portraits de femme en Hermès', Le Monde d’Hermès, Photography by Joanna Van MulderHermès, on the other hand, was among the oldest and grandest French status names of them all. Cheap fashion jokes ensued. Would Margiela whitewash the Kelly bag, for example? He loved white – or whites, in Margiela speak – painting leather, denim and more and celebrating the way the non-colour aged thus reflecting the passing of time.

In fact, Margiela’s appointment by then Hermès CEO, the late Jean-Louis Dumas, was among the most inspired in fashion history. Dumas recognised that, at the heart of it all, Margiela was an unrivalled technician. He also saw that at the centre of the Maison Martin Margiela universe, however extreme any tropes might be, was the woman wearing the clothes. His designs may have been groundbreaking but they considered the body inside them over and above anything else.

Vareuse in double-faced cashmere, sleeveless high-neck pullover in cashmere, mid-length skirt in Shetland wool and boots in calfskin, ‘Le vêtement comme manière de vivre’ Le Monde d’Hermès, Hermès A/W98, Photography by John Midgley

Vareuse in double-faced cashmere, sleeveless high-neck pullover in cashmere, mid-length skirt in Shetland wool and boots in calfskin, ‘Le vêtement comme manière de vivre’ Le Monde d’Hermès, Hermès A/W98, Photography by John MidgleyA new exhibition, Margiela, The Hermès Years, at MoMu in Antwerp, is nothing if not testimony to that. At a press conference held in that city on the eve of the opening, Pierre-Alexis Dumas, Jean-Louis’ son and today artistic director at Hermès, told the story of his father’s meeting with Margiela. In place of the elaborate portfolios and moodboards that might have been expected, the designer gave Jean-Louis Dumas a sequence of words. They were as follows: “Comfort, quality, timelessness, everlasting, handmade, tradition, elegance in movement.” That Dumas was able to embrace such an abstract concept – and that Margiela thought in that way in the first place – is nothing short of visionary on both sides. Margiela wasn’t interested in scarf silks or bright colour, something that might have frightened a less pioneering employer given that both were Hermès signatures. Instead, and way ahead of his time, he was intent on the gradual building of a discreetly beautiful wardrobe for discerning women, of all ages, shapes and sizes, assuming, of course, that their budgets allowed. Pierre-Alexis prefers the adjective “costly” to “expensive”, he says with a smile.

“Comfort, quality, timelessness, everlasting, handmade, tradition, elegance in movement” – Martin Margiela

Collarless jacket and pants in cashmere and silk, high-neck pullover in cashmere and silk, scarf ‘Losange’ in silk crêpe, Le Monde d’Hermès, Hermès A/W01, Photography by Ralph Mecke

Collarless jacket and pants in cashmere and silk, high-neck pullover in cashmere and silk, scarf ‘Losange’ in silk crêpe, Le Monde d’Hermès, Hermès A/W01, Photography by Ralph Meckecont'd...

Last edited: