You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Filters

Show only:

Andiamo Backpack Size

- By noprice923

- Bottega Veneta

- 0 Replies

Has there been an andiamo backpack in a smaller size? I was told there was a 40 cm version in canvas but the only versions of the backpack I can find are around 50 cm.

Coussin PM

- By ottgal

- Louis Vuitton

- 15 Replies

I just purchased the cousin PM in black in Paris. It was advertised heavily as well as the capucine so I think still very on trend. For those who own, how has the wear been? My SA told me it’s coated to protect so durable.

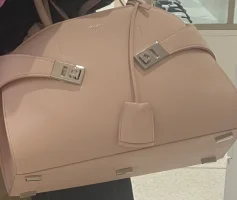

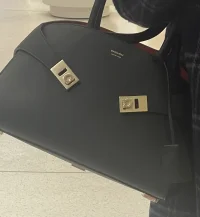

Hug bag color

- By diamond2024

- Ferragamo

- 4 Replies

I am trying to decide between the pink and the black hug bag…both medium size

Black is obviously the classic and the safe choice… but I do have quite a few black bags already although they are not quite the same style. I do like pink but worried about it getting dirty and harder to match…anyone got the same pink color? How is it holding up

Any opinions that can help me to decide would be appreciated 🙏

The black one does have some linear grain running through out which I find odd - perhaps just that particular piece?

(sorry I reposted as hoping for better response. I’ve also posted under the hug bag thread if that’s ok)

Black is obviously the classic and the safe choice… but I do have quite a few black bags already although they are not quite the same style. I do like pink but worried about it getting dirty and harder to match…anyone got the same pink color? How is it holding up

Any opinions that can help me to decide would be appreciated 🙏

The black one does have some linear grain running through out which I find odd - perhaps just that particular piece?

(sorry I reposted as hoping for better response. I’ve also posted under the hug bag thread if that’s ok)

Attachments

Pink Sapphire: Tiffany CBTY vs. Cartier D'Amour?

- The Jewelry Box

- 3 Replies

Hi, folks! I'm interested in a delicate pink sapphire necklace. I'm debating between the 0.08 ct Tiffany Color by the Yard available only in silver and currently out of stock or the Cartier D'Amour pink sapphire in rose gold that Dr. Google tells me is about 0.16 ct. Can anyone comment on which stone is the most highly pigmented pink between the D'Amour and the CBTY? I do currently have a bezel amethyst yellow gold necklace that's about 0.75 ct in size and don't want a pink sapphire that leans purple. I know I love the Elsa Peretti By the Yard collection, but I think pink sapphire might be best served in rose gold like the D'Amour. I'm not concerned with the Tiffany being too tiny, as I have a platinum 0.08 ct DBTY that I love. Any pictures or advice on these pink sapphire options would be greatly appreciated!

Attachments

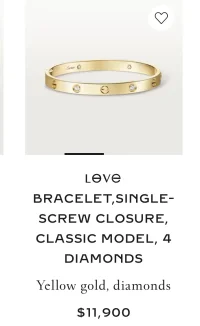

Cartier Love Bracelet - HELP cost of replacement rivets/screws??

Hi All,

Can anyone share the rough cost of replacing the rivets/screws on a Cartier Love bracelet - these are the decorational ones vs the ones on the hinge as per the picture. I have tried asking Cartier customer service and in-store and honestly they're plain useless/rude to me about it and don't seem to be able to provide even a rough price per sku and just say I need to send back the bracelet before they can provide the cost. I think it's a just a money making measure as you are guaranteed to have to pay them $175 just for using this service without the cost of anything else. Anyone got an idea?

Can anyone share the rough cost of replacing the rivets/screws on a Cartier Love bracelet - these are the decorational ones vs the ones on the hinge as per the picture. I have tried asking Cartier customer service and in-store and honestly they're plain useless/rude to me about it and don't seem to be able to provide even a rough price per sku and just say I need to send back the bracelet before they can provide the cost. I think it's a just a money making measure as you are guaranteed to have to pay them $175 just for using this service without the cost of anything else. Anyone got an idea?

Attachments

Feedback please!

- Prada

- 2 Replies

Hi! I’m in the market for a new Crossbody bag and I keep coming back to this Prada. Does anyone have any feedback on it? I don’t want anything too delicate.

I am pretty drawn to the orange color, I feel like it might work kind of as a bold neutral if that makes sense?

Is there any chance this bag will go on sale?

I am pretty drawn to the orange color, I feel like it might work kind of as a bold neutral if that makes sense?

Is there any chance this bag will go on sale?

Barenia Faubourg vs Courchevel for Kelly (Retourne)

- By MamaWagzz

- Hermès Leathers

- 8 Replies

Hi Ladies,

I’m not an Hermes leather expert and looking for some advice. Anyone here have owned and experienced both Courchevel and Barenia Faubourg (particularly K25 or K28 Retourne)? How do these two leathers age? How do these two leathers compared in terms of look and feel? Can the corners be refurnished or repaired by Hermes spa? Which leather would you prefer more? Thank you so much! 😊

I’m not an Hermes leather expert and looking for some advice. Anyone here have owned and experienced both Courchevel and Barenia Faubourg (particularly K25 or K28 Retourne)? How do these two leathers age? How do these two leathers compared in terms of look and feel? Can the corners be refurnished or repaired by Hermes spa? Which leather would you prefer more? Thank you so much! 😊

Craie RGH vs Gris Perle RGH/Gold Togo Birkin

- Hermès

- 1 Replies

I have always dreamed of having Craie RGH Togo Birkin but ended up with the following Birkins listed below:

1. Beton Touch Togo B30 in Palladium hardware

2. Black Togo B30 in Gold hardware

3. Fauve Barenia Faubourg B30 in Gold hardware

4. Kelly 28 in Etoupe epsom

I have never seen Craie RGH or Gris Perle in person but fell in love with it through pictures images. I am considering it for my next quota bag. I am 5’3, medium built at 135 lbs in 50’s. Pretty fair skin tone with Burnett hair color. Neutral to closer to warm tone skin.

It seems like Craie is lighter shade than Beton but what about Gris Perle? Is it a shade in between Craie and Beton? Please help me to choose from the following list for my next quota Birkin (or any other good suggestions you may have):

1. Go for Craie RGH in B 25 or B30?

2. Go for Gris Perle in RGH/ Gold hardware (which hardware looks better? ) in B25 or B30? (Is Gris Perle shade in between Craie & Beton?)

3. Go for other colors such as Etain Togo RGH in B20 or B30?

4. Etoup Togo in palladium?

Can’t decide but it would be very helpful if you can help me to decide for my next quota bag request. Thank you so much ina dance.

1. Beton Touch Togo B30 in Palladium hardware

2. Black Togo B30 in Gold hardware

3. Fauve Barenia Faubourg B30 in Gold hardware

4. Kelly 28 in Etoupe epsom

I have never seen Craie RGH or Gris Perle in person but fell in love with it through pictures images. I am considering it for my next quota bag. I am 5’3, medium built at 135 lbs in 50’s. Pretty fair skin tone with Burnett hair color. Neutral to closer to warm tone skin.

It seems like Craie is lighter shade than Beton but what about Gris Perle? Is it a shade in between Craie and Beton? Please help me to choose from the following list for my next quota Birkin (or any other good suggestions you may have):

1. Go for Craie RGH in B 25 or B30?

2. Go for Gris Perle in RGH/ Gold hardware (which hardware looks better? ) in B25 or B30? (Is Gris Perle shade in between Craie & Beton?)

3. Go for other colors such as Etain Togo RGH in B20 or B30?

4. Etoup Togo in palladium?

Can’t decide but it would be very helpful if you can help me to decide for my next quota bag request. Thank you so much ina dance.

New Collab: Carter Panthère C de Cartier bag

Last month, we collaborated with Cartier on their Panthère C de Cartier Collection of bags. We're really proud of how it came out, you can read the full article here:

Cartier’s Panthère Comes to Life - PurseBlog

The mere thought of adding the right bag to your wardrobe opens up endless possibilities. It completes a dream in a way, a vision of ourselves as the person we want the world to see. When a bag goes…

Let us know what you think!

Is there a way to fix silver colored hardware on a vintage bag?

- By handtasche

- Bottega Veneta

- 0 Replies

I just purchased a vintage bottega veneta in just very very good condition. It’s such a cute little piece- the only wear you can see is on the closure. Is there a way to repaint it? Or did some one try to take anything of, so that the color is more even? I don’t think that BV can repair/ exchange the little thing. It’s way too old. I saw other bags on the secondary market and they all have alt least this issue 😃🤭. Thank you.

Attachments

Lizard vs Galuchat

- By diamond2024

- Fendi

- 7 Replies

Hello,

Just wondering whether anyone owns both the Fendi peekaboo in lizard as well as the Galuchat?

Or else, any opinions on which one is better/easier to maintain for long term?

I am trying to decide on my first exotics!

Thanks

Just wondering whether anyone owns both the Fendi peekaboo in lizard as well as the Galuchat?

Or else, any opinions on which one is better/easier to maintain for long term?

I am trying to decide on my first exotics!

Thanks

Chrome hearts authentication

- By storeberry

- The Jewelry Box

- 1 Replies

Hi all, just bought a Chrome heart glasses but questioning the authenticity. Anyone can point me to a company that does authentication for Chrome Hearts glasses? Thanks!

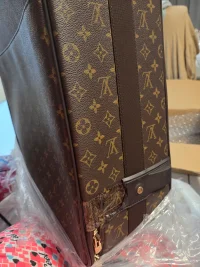

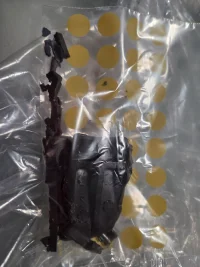

Pegasse 55 ruined

- By bravorodrig

- Louis Vuitton Reference Library

- 16 Replies

Hi. I bought a preloved Pegasse 55 from ZenLuxe. My first ever purchase from them and I was very weary and hesitant. My 50th bday is next week and my husband told me to get it. I'm not exaggerating when I say I thought it over for two weeks.

It finally arrived today and all my worries were absolutely warranted. It's, I can't even find the words, messed up. The plastic on the stubs on the side is shattered. Its sticky and kind of disintegrating. It didn't look like this or like it was broken or in bad shape in the listing and obviously its been taken down. And I looked very closely at it because I thought the zipper in that corner was damaged.

The rest of the suitcase looks ok. The vachetta has some water stains which I expected. It came with the dustbag and one of the elastics on the inside is also broken (but an easy fix, I think). But that plastic is beyond repair.

Anyone ever dealt with them before? I already messaged them but frankly I'm not expecting much. Any suggestions and ideas are more than welcome. I'm so bummed. 😩

It finally arrived today and all my worries were absolutely warranted. It's, I can't even find the words, messed up. The plastic on the stubs on the side is shattered. Its sticky and kind of disintegrating. It didn't look like this or like it was broken or in bad shape in the listing and obviously its been taken down. And I looked very closely at it because I thought the zipper in that corner was damaged.

The rest of the suitcase looks ok. The vachetta has some water stains which I expected. It came with the dustbag and one of the elastics on the inside is also broken (but an easy fix, I think). But that plastic is beyond repair.

Anyone ever dealt with them before? I already messaged them but frankly I'm not expecting much. Any suggestions and ideas are more than welcome. I'm so bummed. 😩

Attachments

-

20250715_180758.webp230.1 KB · Views: 79

20250715_180758.webp230.1 KB · Views: 79 -

20250715_180803.webp224 KB · Views: 79

20250715_180803.webp224 KB · Views: 79 -

20250715_181311.webp154.9 KB · Views: 68

20250715_181311.webp154.9 KB · Views: 68 -

20250715_181006.webp180.4 KB · Views: 63

20250715_181006.webp180.4 KB · Views: 63 -

20250715_180833.webp60.5 KB · Views: 62

20250715_180833.webp60.5 KB · Views: 62 -

20250715_180835.webp50.6 KB · Views: 64

20250715_180835.webp50.6 KB · Views: 64 -

20250715_182014.webp82 KB · Views: 67

20250715_182014.webp82 KB · Views: 67 -

20250715_183450.webp238.7 KB · Views: 67

20250715_183450.webp238.7 KB · Views: 67 -

20250715_183453.webp259.5 KB · Views: 67

20250715_183453.webp259.5 KB · Views: 67 -

20250715_183539.webp175.1 KB · Views: 62

20250715_183539.webp175.1 KB · Views: 62 -

20250715_184551.webp82 KB · Views: 74

20250715_184551.webp82 KB · Views: 74

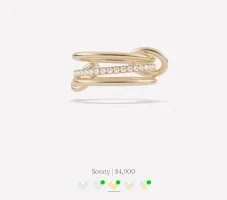

Cartier Love bracelet or Spinelli Kilcollin Ring

- By mimingkat

- The Jewelry Box

- 7 Replies

Hi All, this is my main stack and I don’t know if I should get the Spinelli Kilcollin Ring or the love bangle 4 diamonds. I usually gravitate towards edgier look. I MIGHT end up getting both eventually but which one you think I should get first?

Thank you!

Thank you!

Attachments

Sombrero leather repair

- By dipinky

- Hermès Leathers

- 0 Replies

Hi everyone I have for a sombrero Kelly 32 and due to pressure from a metal object, it left a very shallow indentation on the leather. About 1cm long. I read posts where heat is applied to restore the indentation. Is it safe to do so on the sombrero leather? Thank you!

Barenia Evelyne and vintage Chanel question

- By CaviarChanel

- Handbag Care & Maintenance

- 5 Replies

Hi All,

I need advice :

1) Can I treat the Evelyne with Saphir leather balm OR Lexol conditioner OR drop off at Hermes Spa for some tender care? Stains are

likely from food while I was having my meals 😳

2) Here is my vintage ( lambskin/calf leather?) Chanel - condition or do nothing?

Any input will be greatly appreciated. 😘

I need advice :

1) Can I treat the Evelyne with Saphir leather balm OR Lexol conditioner OR drop off at Hermes Spa for some tender care? Stains are

likely from food while I was having my meals 😳

2) Here is my vintage ( lambskin/calf leather?) Chanel - condition or do nothing?

Any input will be greatly appreciated. 😘

Attachments

Loose Hardware on Roulis?

I am considering purchasing a preloved Roulis. The (online) seller has shared that the hardware on the strap is loose (photo below), pulling away from the leather.

Does anyone have experience with this sort of hardware loosening on a Roulis? The other side of the hardware (inside the bag) is hidden beneath leather, so it's not clear to me how the two pieces connect. Is it a screw type attachment? That would be an easy fix that would just require tightening by rotating the strap. If it's something else it would presumably require unstitching and restitching the leather.

I'll happily take it in to H to be fixed, but I'd love a sense of whether this is easily fixable, and what the cost might run, before I purchase.

Does anyone have experience with this sort of hardware loosening on a Roulis? The other side of the hardware (inside the bag) is hidden beneath leather, so it's not clear to me how the two pieces connect. Is it a screw type attachment? That would be an easy fix that would just require tightening by rotating the strap. If it's something else it would presumably require unstitching and restitching the leather.

I'll happily take it in to H to be fixed, but I'd love a sense of whether this is easily fixable, and what the cost might run, before I purchase.

New to me Chanel 19 tweed- opinions

Was stalking this bag since seeing it in 2021.

I love the color and pattern tho it’s not “trendy”.

Is this a delicate tweed ? I didn’t think so but not sure.

Thanks !

I love the color and pattern tho it’s not “trendy”.

Is this a delicate tweed ? I didn’t think so but not sure.

Thanks !

Attachments

Panthere watch or JUC bracelet?

- By beesknees2

- Cartier

- 18 Replies

I'm excited to pick between the two toned Panthere watch (small) and the YG JUC bracelet (regular) for a special occasion gift. I already have a stainless steel Tank Francaise, a YG Love cuff, and a YG Love ring. The Panthere and JUC have both been on my list for a while, and both would go well with my current collection.

Panthere pros:

- tie together my yellow gold jewelry and platinum wedding set

- goes with my overall aesthetic (minimalist, love the 90s vibe of the watch)

- versatile - can wear to work

Panthere cons:

- not sure if I need two Cartier watches (I still really love my Tank Francaise)

- too popular? Every Instagram/TikTok influencer seems to wear one these days

JUC pros:

- stacks well with my Love cuff

- love the look of it

- can leave on 24/7

JUC cons:

- a bit bold for my aesthetic (I'm petite and don't really wear "loud" jewelry)

- too eye-catching to comfortably wear to work

Please let me know what your thoughts are. TIA!

Panthere pros:

- tie together my yellow gold jewelry and platinum wedding set

- goes with my overall aesthetic (minimalist, love the 90s vibe of the watch)

- versatile - can wear to work

Panthere cons:

- not sure if I need two Cartier watches (I still really love my Tank Francaise)

- too popular? Every Instagram/TikTok influencer seems to wear one these days

JUC pros:

- stacks well with my Love cuff

- love the look of it

- can leave on 24/7

JUC cons:

- a bit bold for my aesthetic (I'm petite and don't really wear "loud" jewelry)

- too eye-catching to comfortably wear to work

Please let me know what your thoughts are. TIA!

Bvlgari high jewelry

The most beautiful Bvlgari high jewelry necklace I have seen in social media so far. Love the matching earrings.

From Rebecca Bloom’s instagram account.

Login to view embedded media

From Rebecca Bloom’s instagram account.

Login to view embedded media

The ultimate burgundy/maroon shoulder bag

- By baglover2000

- Handbags & Purses

- 16 Replies

Hi everyone! I wanted to get opinions from other fashion and luxury lovers and thought it would be a good idea to start this discussion. I'm looking for a shoulder bag that's easy to use, on the go and can fit more than just a phone and lip gloss. Something to wear throughout the day or from early morning to early evening, and in the colour burgundy/maroon/crimson/bordeaux (whatever you wanna call it) with a leather strap! When I saw the Kelly Elan in Rouge H, I died and knew that was the perfect bag! Without being able to score it or having the budget to buy it from the grey market, I decided to find the next best alternative that isn't a dupe but still a 'designer luxury bag'. These are some of the options I'm contemplating and wanted your guys' opinion on the best 'ultimate' shoulder bag.

1. Bottega Veneta hop small: https://www.bottegaveneta.com/en-gb/hop-barolo-796262V3IV12250.html

2. Bottega Veneta andiamo small: https://www.bottegaveneta.com/en-gb/small-andiamo-barolo-766014VCPP12273.html (Not the best shoulder bag but love the versatility of it)

3. Alaia le teckle medium: https://www.maison-alaia.com/gb/shoulder-bag_cod45894814jl.html

4. Prada bonnie medium: https://www.prada.com/gb/en/p/prada-bonnie-small-leather-shoulder-bag/1BA426_2CYR_F0LV7_V_MOO

5. YSL Le 5 a 7: https://www.ysl.com/en-gb/pr/le-5-a-7-in-patent-leather-813233290.html

Would love all your opinions on more options, the ultimate one for you and which you'd get out of these 5 options

1. Bottega Veneta hop small: https://www.bottegaveneta.com/en-gb/hop-barolo-796262V3IV12250.html

2. Bottega Veneta andiamo small: https://www.bottegaveneta.com/en-gb/small-andiamo-barolo-766014VCPP12273.html (Not the best shoulder bag but love the versatility of it)

3. Alaia le teckle medium: https://www.maison-alaia.com/gb/shoulder-bag_cod45894814jl.html

4. Prada bonnie medium: https://www.prada.com/gb/en/p/prada-bonnie-small-leather-shoulder-bag/1BA426_2CYR_F0LV7_V_MOO

5. YSL Le 5 a 7: https://www.ysl.com/en-gb/pr/le-5-a-7-in-patent-leather-813233290.html

Would love all your opinions on more options, the ultimate one for you and which you'd get out of these 5 options

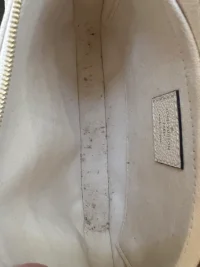

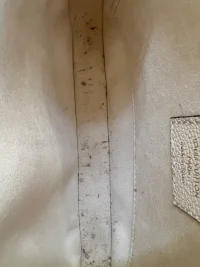

Is this mold inside my LV?

- By reelee1004

- Louis Vuitton Reference Library

- 7 Replies

I don’t know if this is makeup or mold. I just opened my LV pochette accessories emprient and I noticed these faint grey-ish spots. I used the bag six weeks ago at a wedding and I can’t remember if I had makeup in my bag and I honestly don’t remember noticing the spots at the time when I emptied my bag and put it away at the end of that night. I store my bags in my closet in a LBD Case (brand is Luxury Bag Display and they make acrylic storage displays that “provide protection from dust, humidity, light/UV damage. It prevents stain, mildew, and significantly cuts down harmful UV that causes fading and discoloration. Essential for leather care, LBD cases also allow leather to "breathe", with innovative design that ensures air circulation.”)

Since I can’t recall what my bag looked like the last time I used it, I don’t know if I’m going crazy thinking it’s mold or if it’s actually mold. The mini Pochette that accompanies this bag is perfectly fine and I store them together. Outside of the bag looks perfectly fine too.

Since I can’t recall what my bag looked like the last time I used it, I don’t know if I’m going crazy thinking it’s mold or if it’s actually mold. The mini Pochette that accompanies this bag is perfectly fine and I store them together. Outside of the bag looks perfectly fine too.

Attachments

Purchasing shoes from Nordstrom and CHANEL & Moi?

- By aaariel

- Chanel Shopping

- 8 Replies

Hello all! I made my first chanel shoes purchase today at a Nordstrom store. It’s a remote purchase and the shoes will be shipped to me. I’ve received a receipt from Nordstrom but not Chanel’s. My question is, is my purchase covered by the Chanel & Moi program? If not and if I wanted it to, do I have to buy directly from a Chanel boutique instead of a department store? Any insights appreciated!

Article on Superfakes (sigh)

- By snibor

- Handbags & Purses

- 9 Replies

Article from Wall Street Journal by Carol Ryan. I hate this! Why don’t they just direct people to where to buy illegal superfakes (sarcasm). Didn’t know if a link would show so I printed it here.

“Inside the Shadowy, Lucrative Business of ‘Superfake’ Luxury Handbags”

Sandor Walkup was waiting for a table at an expensive restaurant in Charlotte, N.C., when he noticed a woman checking out his Himalayan Birkin. It is a rare crocodile-skin handbag that maker Hermès charges tens of thousands of dollars for and only sells to top clients.

“As I was walking through the restaurant she stopped me and said, ‘I love your bag, it’s the perfect size. It probably cost you a fortune.’”

When the woman asked if he would consider an offer for it, Walkup, a TikTok influencer, leveled with her: “Ma’am, the bag is a fake.” The woman was surprised at how convincing the Birkin was and asked where she could buy one for herself. So he gave her the details of a private dealer who sells top-notch fakes.

Related video: 'Icon of our time': Jane Birkin’s original Hermès bag sells at auction for 8.6 million euros (The Associated Press)

Related video: 'Icon of our time': Jane Birkin’s original Hermès bag sells at auction for 8.6 million euros (The Associated Press)

Play Video

The Associated Press

The Associated Press

'Icon of our time': Jane Birkin’s original Hermès bag sells at auction for 8.6 million euros

Unmute

View on Watch

Counterfeiters have perfected the knockoff handbag—and it is disrupting the economics of the luxury industry. Fake purses have always been around, but they were the cheap and plasticky kind that could be picked up for a few bucks from a sidewalk seller.

A new generation of “superfakes,” as they are known in the industry, look as good as the real thing and cost anywhere from $500 to $5,000. Counterfeiters take your order through encrypted services such as WhatsApp or Telegram, give real-time customer service and deliver the goods straight to your door in a branded box.

They pay social-media influencers to promote illicit goods directly to American and European consumers. The technique is proving so good at sanitizing counterfeiters’ shady image that the language used to talk about the bags is changing. The word “fake” isn’t used anymore. Instead, fans call the purses replicas, mirror bags, superclones or 1:1s (“one to ones”).

In a red flag for luxury brands, young shoppers are embracing the superfakes. A social-media storm erupted in April when Chinese counterfeiters posted videos claiming that major luxury brands are secretly manufacturing their handbags for next to nothing in China. In most cases, the claims made in the videos are bogus.

But the posts reinforced doubts in the minds of Gen Z consumers about the industry’s steep markups and whether people who buy genuine luxury goods are getting a raw deal. Popular handbags such as a Lady Dior sell for up to 15 times what they cost to manufacture, according to Bernstein, a brokerage.

Buying a replica is becoming a way “to give big brands the middle finger,” says Marian Makkar, a luxury marketing expert based in Australia who has researched the superfake phenomenon.

There are early signs that young shoppers’ cooling attitude toward authentic luxury is hitting the industry’s top line. Last year, Gen Z shoppers spent roughly $5 billion less on luxury brands than they did in 2023, data from consulting firm Bain & Co. shows. This might simply be a sign they are feeling pinched by rising bills, or that they are defecting to fakes in high numbers.

The attitude shift about superfakes is a gift to counterfeiters who now market their goods as a financially savvy alternative to overpriced luxury brands: Why pay $11,000 for an authentic Chanel classic flap purse when you can get a near-identical $600 replica from a Chinese factory that claims to source its leather from the same European supplier as the Parisian brand?

People in the secondhand-luxury business first noticed a new strain of counterfeits around five years ago. Some of the superfake handbags were so good that they couldn’t be spotted with the naked eye.

Luxury resale website Fashionphile has a counterfeit Louis Vuitton handbag on display alongside a real one at its New York flagship store—an “authenticity challenge” to see if shoppers can spot the real from the fake. The company’s founder Sarah Davis says people who work as sales assistants for top luxury brands haven’t been able to tell the bags apart.

Rival reseller The RealReal had to invest in XRF technology to test the metal composition of handbags’ buckles to spot the new fakes. The company also bought X-ray machines to examine their innards. Counterfeiters have perfected the outside of the bags, but might still leave a trace on the inside, according to Hunter Thompson, director of authentication at The RealReal. “It could be a tiny detail such as how a nail head is hammered in.”

Anticounterfeit professionals have theories about how the fakes got so good. One is industrial theft. Luxury brands store the instructions about how to make authentic handbags on digital templates known as tech packs.

These master manuals contain an excel spreadsheet with the purse’s exact measurements, a technical drawing, details of the threads, trimmings and leather used, and even the precise number of stitches per seam. If a brand’s tech pack falls into the wrong hands, counterfeiters can easily make a carbon copy. The risk that this information leaks out of a factory has risen as brands outsource more production.

Counterfeiters also try to poach workers from genuine factories to get inside knowledge. People who stitch luxury handbags for a living earn a decent but not extravagant wage, so might have their head turned by an offer from an illicit manufacturer.

Hermès pays its France-based handbag artisans the equivalent of $40,000 a year including bonus payouts, based on Glass Door salary reviews. That is less than what the brand charges its U.S. customers for a single crocodile Birkin handbag. Some of the company’s former employees were convicted in 2020 for running a counterfeit ring outside their day job.

Most fakes are still made the old-fashioned way: A counterfeiter buys an authentic bag, rips it apart to see how it’s made and then reverse engineers a fake.

The best superfake purses are often produced in factories in China that run legitimate businesses for mass-market fashion retailers during the day, according to James Godefroy, a Guangzhou-based investigator with brand-protection agency Rouse. By night, a ghost shift produces knockoffs.

Counterfeiters boost demand by paying social-media personalities to review fake handbags. The feed of one Instagram account, @davidslifestyle, is full of videos of counterfeit unboxings. Followers can click a link to the influencer’s direct.me page, where they will find affiliate links to more than 150 fake goods including Louis Vuitton Neverfull totes and Hermès Birkin bags.

The links lead to a Hong Kong-based website called Save Bullet. The influencer earns 10% from any sale his videos generate, based on information about Save Bullet’s affiliate program. So in the case of a $789 fake yellow Hermès Birkin, the influencer pockets nearly $80 for every bag his followers order.

@davidslifestyle said that he reviewed real as well as replica luxury goods on his channel, and bought authentic products until a year-and-a-half ago, when he felt the quality went down.

Counterfeiters’ new online-distribution model is a nightmare for luxury brands. Fake handbags once arrived at customs ports in big shipments, making them easier to intercept. Now that counterfeiters sell directly to consumers, a tide of individual packages is overwhelming customs authorities and slipping past checks.

Luxury brands pay private investigators to gather information about what counterfeiters are up to. They open fake accounts on online forums where counterfeiters do business and go undercover in factories.

Investigators like to watch a freewheeling Reddit community called RepladiesDesigner that has over 200,000 members. Fans of the fake bags share China or Hong Kong-based WhatsApp numbers for recommended sellers and post photos of their latest purchases. Reddit said in a statement that it may ban any subreddit where it is clear the community is “dedicated to violative content.”

Counterfeiters are moving to private Instagram or invite-only Telegram groups that are harder for luxury brands to track. “It is like joining a golf club now,” says Jak Cluness, vice president of intelligence and investigations at brand-protection company Corsearch. “You have to be recommended by another member to get in.” He is tracking a WhatsApp group that uses a subscription-based model charging members $98 a month to get access to the best-quality fakes.

A counterfeit dealer who goes by Heidi said in a text interview that she works for several factories that each specialize in a different brand. A fake Hermès Birkin 25 in Togo leather from a place she called the Hidden Star factory will set you back $1,800. Prices for counterfeit Birkins in exotic skins such as crocodile start at $4,000 compared with more than $50,000 for the genuine bag.

For a counterfeit Chanel classic flap purse, the seller recommended the 187 Factory. Its $575 fakes have proven so popular that there are even “fake” 187 superfakes. Rival counterfeiters pose as the factory but send an inferior knockoff.

Online sellers are usually freelance operators who reel in customers with details such as the accuracy of the stitching and whether the seams line up properly, according to Cluness. They even send quality-control videos of the counterfeits to make sure the shopper is satisfied with their bag before it ships. A busy freelance seller can make anywhere from $5,000 to $20,000 a month in commission.

Counterfeit factories also make fat profits. A top-quality fake costs around $150 to produce in China, including labor and materials. Operating margins can be 50% or higher if the factory handles its own sales directly. Genuine luxury brands are lucky to make a 40% operating margin on handbags, as they have to spend on fancy stores, living wages and multibillion-dollar advertising budgets.

A Guangzhou-based counterfeit factory owner who goes by the surname Li says he makes a profit of $450 per fake Hermès bag, and sells roughly three hundred a month. He recently spent more than $70,000 to acquire three genuine purses as templates—a Birkin 30 bag, a Mini Kelly II, and a Himalayan Birkin 25. He is disassembling them on a cutting table to create patterns for fakes.

He calls people who pay full price for genuine luxury goods “stupid and vain.” His own customers can be high-maintenance. “A person who buys a knockoff is often very thin-skinned and very nitpicky,” he said.

Brands sometimes see counterfeits as a gateway drug that will eventually lead shoppers to buy the genuine article. Briege Elder, a London-based PR manager with Hunt & Gather agency who used to work as a sales assistant at Louis Vuitton and Gucci, said people regularly came to the brands’ stores carrying fake handbags.

It was an unspoken rule not to call out a knockoff. “We would never address a fake product, ever. Not if it was the worst fake in the world or the best.” People carrying a fake were treated as aspiring customers. “They have a counterfeit today, but they might become a customer in future,” Elder says.

Brands’ relatively small anticounterfeit budgets suggest they aren’t yet seriously worried about the superfake phenomenon. LVMH, the biggest luxury company in the world, spent more than $11 billion on advertising last year but only $45 million on anticounterfeit efforts. That seems skimpy. Superfakes counterfeiters are becoming real competitors.

Write to Carol Ryan at [email protected]Produced by Alexandra Citrin-Safadi

Sponsored Content

“Inside the Shadowy, Lucrative Business of ‘Superfake’ Luxury Handbags”

Sandor Walkup was waiting for a table at an expensive restaurant in Charlotte, N.C., when he noticed a woman checking out his Himalayan Birkin. It is a rare crocodile-skin handbag that maker Hermès charges tens of thousands of dollars for and only sells to top clients.

“As I was walking through the restaurant she stopped me and said, ‘I love your bag, it’s the perfect size. It probably cost you a fortune.’”

When the woman asked if he would consider an offer for it, Walkup, a TikTok influencer, leveled with her: “Ma’am, the bag is a fake.” The woman was surprised at how convincing the Birkin was and asked where she could buy one for herself. So he gave her the details of a private dealer who sells top-notch fakes.

Play Video

'Icon of our time': Jane Birkin’s original Hermès bag sells at auction for 8.6 million euros

Unmute

View on Watch

Counterfeiters have perfected the knockoff handbag—and it is disrupting the economics of the luxury industry. Fake purses have always been around, but they were the cheap and plasticky kind that could be picked up for a few bucks from a sidewalk seller.

A new generation of “superfakes,” as they are known in the industry, look as good as the real thing and cost anywhere from $500 to $5,000. Counterfeiters take your order through encrypted services such as WhatsApp or Telegram, give real-time customer service and deliver the goods straight to your door in a branded box.

They pay social-media influencers to promote illicit goods directly to American and European consumers. The technique is proving so good at sanitizing counterfeiters’ shady image that the language used to talk about the bags is changing. The word “fake” isn’t used anymore. Instead, fans call the purses replicas, mirror bags, superclones or 1:1s (“one to ones”).

In a red flag for luxury brands, young shoppers are embracing the superfakes. A social-media storm erupted in April when Chinese counterfeiters posted videos claiming that major luxury brands are secretly manufacturing their handbags for next to nothing in China. In most cases, the claims made in the videos are bogus.

But the posts reinforced doubts in the minds of Gen Z consumers about the industry’s steep markups and whether people who buy genuine luxury goods are getting a raw deal. Popular handbags such as a Lady Dior sell for up to 15 times what they cost to manufacture, according to Bernstein, a brokerage.

Buying a replica is becoming a way “to give big brands the middle finger,” says Marian Makkar, a luxury marketing expert based in Australia who has researched the superfake phenomenon.

There are early signs that young shoppers’ cooling attitude toward authentic luxury is hitting the industry’s top line. Last year, Gen Z shoppers spent roughly $5 billion less on luxury brands than they did in 2023, data from consulting firm Bain & Co. shows. This might simply be a sign they are feeling pinched by rising bills, or that they are defecting to fakes in high numbers.

The attitude shift about superfakes is a gift to counterfeiters who now market their goods as a financially savvy alternative to overpriced luxury brands: Why pay $11,000 for an authentic Chanel classic flap purse when you can get a near-identical $600 replica from a Chinese factory that claims to source its leather from the same European supplier as the Parisian brand?

People in the secondhand-luxury business first noticed a new strain of counterfeits around five years ago. Some of the superfake handbags were so good that they couldn’t be spotted with the naked eye.

Luxury resale website Fashionphile has a counterfeit Louis Vuitton handbag on display alongside a real one at its New York flagship store—an “authenticity challenge” to see if shoppers can spot the real from the fake. The company’s founder Sarah Davis says people who work as sales assistants for top luxury brands haven’t been able to tell the bags apart.

Rival reseller The RealReal had to invest in XRF technology to test the metal composition of handbags’ buckles to spot the new fakes. The company also bought X-ray machines to examine their innards. Counterfeiters have perfected the outside of the bags, but might still leave a trace on the inside, according to Hunter Thompson, director of authentication at The RealReal. “It could be a tiny detail such as how a nail head is hammered in.”

Anticounterfeit professionals have theories about how the fakes got so good. One is industrial theft. Luxury brands store the instructions about how to make authentic handbags on digital templates known as tech packs.

These master manuals contain an excel spreadsheet with the purse’s exact measurements, a technical drawing, details of the threads, trimmings and leather used, and even the precise number of stitches per seam. If a brand’s tech pack falls into the wrong hands, counterfeiters can easily make a carbon copy. The risk that this information leaks out of a factory has risen as brands outsource more production.

Counterfeiters also try to poach workers from genuine factories to get inside knowledge. People who stitch luxury handbags for a living earn a decent but not extravagant wage, so might have their head turned by an offer from an illicit manufacturer.

Hermès pays its France-based handbag artisans the equivalent of $40,000 a year including bonus payouts, based on Glass Door salary reviews. That is less than what the brand charges its U.S. customers for a single crocodile Birkin handbag. Some of the company’s former employees were convicted in 2020 for running a counterfeit ring outside their day job.

Most fakes are still made the old-fashioned way: A counterfeiter buys an authentic bag, rips it apart to see how it’s made and then reverse engineers a fake.

The best superfake purses are often produced in factories in China that run legitimate businesses for mass-market fashion retailers during the day, according to James Godefroy, a Guangzhou-based investigator with brand-protection agency Rouse. By night, a ghost shift produces knockoffs.

Counterfeiters boost demand by paying social-media personalities to review fake handbags. The feed of one Instagram account, @davidslifestyle, is full of videos of counterfeit unboxings. Followers can click a link to the influencer’s direct.me page, where they will find affiliate links to more than 150 fake goods including Louis Vuitton Neverfull totes and Hermès Birkin bags.

The links lead to a Hong Kong-based website called Save Bullet. The influencer earns 10% from any sale his videos generate, based on information about Save Bullet’s affiliate program. So in the case of a $789 fake yellow Hermès Birkin, the influencer pockets nearly $80 for every bag his followers order.

@davidslifestyle said that he reviewed real as well as replica luxury goods on his channel, and bought authentic products until a year-and-a-half ago, when he felt the quality went down.

Counterfeiters’ new online-distribution model is a nightmare for luxury brands. Fake handbags once arrived at customs ports in big shipments, making them easier to intercept. Now that counterfeiters sell directly to consumers, a tide of individual packages is overwhelming customs authorities and slipping past checks.

Luxury brands pay private investigators to gather information about what counterfeiters are up to. They open fake accounts on online forums where counterfeiters do business and go undercover in factories.

Investigators like to watch a freewheeling Reddit community called RepladiesDesigner that has over 200,000 members. Fans of the fake bags share China or Hong Kong-based WhatsApp numbers for recommended sellers and post photos of their latest purchases. Reddit said in a statement that it may ban any subreddit where it is clear the community is “dedicated to violative content.”

Counterfeiters are moving to private Instagram or invite-only Telegram groups that are harder for luxury brands to track. “It is like joining a golf club now,” says Jak Cluness, vice president of intelligence and investigations at brand-protection company Corsearch. “You have to be recommended by another member to get in.” He is tracking a WhatsApp group that uses a subscription-based model charging members $98 a month to get access to the best-quality fakes.

A counterfeit dealer who goes by Heidi said in a text interview that she works for several factories that each specialize in a different brand. A fake Hermès Birkin 25 in Togo leather from a place she called the Hidden Star factory will set you back $1,800. Prices for counterfeit Birkins in exotic skins such as crocodile start at $4,000 compared with more than $50,000 for the genuine bag.

For a counterfeit Chanel classic flap purse, the seller recommended the 187 Factory. Its $575 fakes have proven so popular that there are even “fake” 187 superfakes. Rival counterfeiters pose as the factory but send an inferior knockoff.

Online sellers are usually freelance operators who reel in customers with details such as the accuracy of the stitching and whether the seams line up properly, according to Cluness. They even send quality-control videos of the counterfeits to make sure the shopper is satisfied with their bag before it ships. A busy freelance seller can make anywhere from $5,000 to $20,000 a month in commission.

Counterfeit factories also make fat profits. A top-quality fake costs around $150 to produce in China, including labor and materials. Operating margins can be 50% or higher if the factory handles its own sales directly. Genuine luxury brands are lucky to make a 40% operating margin on handbags, as they have to spend on fancy stores, living wages and multibillion-dollar advertising budgets.

A Guangzhou-based counterfeit factory owner who goes by the surname Li says he makes a profit of $450 per fake Hermès bag, and sells roughly three hundred a month. He recently spent more than $70,000 to acquire three genuine purses as templates—a Birkin 30 bag, a Mini Kelly II, and a Himalayan Birkin 25. He is disassembling them on a cutting table to create patterns for fakes.

He calls people who pay full price for genuine luxury goods “stupid and vain.” His own customers can be high-maintenance. “A person who buys a knockoff is often very thin-skinned and very nitpicky,” he said.

Brands sometimes see counterfeits as a gateway drug that will eventually lead shoppers to buy the genuine article. Briege Elder, a London-based PR manager with Hunt & Gather agency who used to work as a sales assistant at Louis Vuitton and Gucci, said people regularly came to the brands’ stores carrying fake handbags.

It was an unspoken rule not to call out a knockoff. “We would never address a fake product, ever. Not if it was the worst fake in the world or the best.” People carrying a fake were treated as aspiring customers. “They have a counterfeit today, but they might become a customer in future,” Elder says.

Brands’ relatively small anticounterfeit budgets suggest they aren’t yet seriously worried about the superfake phenomenon. LVMH, the biggest luxury company in the world, spent more than $11 billion on advertising last year but only $45 million on anticounterfeit efforts. That seems skimpy. Superfakes counterfeiters are becoming real competitors.

Write to Carol Ryan at [email protected]Produced by Alexandra Citrin-Safadi

Sponsored Content

Load more